Guest Post: Nonfiction as influence by Max Gladstone

Guest Post: Nonfiction as influence by Max Gladstone

Writers are quick to name other writers as influences—often

writers working in the same genre. I've

done this time and again, and I could do it here—talk about how important

Zelazny and Dunnet and McKinley and Pratchett and Simmons have been for me

throughout my reading and writing life. But

some books and writers more rarely get a mention: writers of

nonfiction—cultural criticism and history and anthropology and economics—who

have caused me to see the world where I live, and the worlds I write, in

different ways. So, here's a list of a

different kind of influences:

•Jonathan Spence, God's

Chinese Son—Spence is a hugely influential and popular writer on Chinese

history, and learning about the Taiping Rebellion in his class impressed upon

me the utter weirdness of the real world.

Did you know that a (sort of) evangelical Christian (kinda) socialist

movement arose in China in the 19th century to rebel against the

Qing Dynasty in a civil war that left something like twenty million people

dead? Did you know that ostensibly

Christian Western businessfolk raised a mercenary company to support the Qing

rulers in their war against these Taiping revolutionaries? Did you know that the Taiping capital city of

Nanjing was ground zero for a horror show of ex cathedra backstabbing between

three leaders who claimed to be Jesus' younger brother, a personal

representative of God the Father, and a living incarnation of the Holy

Spirit? Well, I didn't. Also

worth reading, if you can find a copy: The

Taiping Revolutionary Movement, by Jen Yu-wen, a comprehensive and profound

and very difficult to locate summary

of the author's shelf full of Chinese-language research into the Taiping. Stephen R Platt's Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom, also on the Taiping, is supposed to

be great—I'm regrettably behind in my reading of it, but I won't be for long.

•James C Scott, Seeing

Like a State—Scott, in this book, skewers the common false equivalence

between "schematically clear" and "good." People, and especially governments, tend to

replace complex systems that work but aren't easily surveilled or controlled

with simpler, more "legible" systems that may be in the interest of

power but are rarely in the interest of the society. The classic example is a monoculture tree

farm compared to a forest: the tree farm has higher lumber yields, yes, but

stands vulnerable to monoculture pests, and anyway doesn't serve the same role

as the forest it replaced. You can't

hunt game in a tree farm, or harvest herbs, or pick berries.

The book ranges from urban design to agriculture to the

development of surnames. Le Corbusier

appears in these pages as a sort of ideological supervillain, sprinting around

the world destroying living cities and replacing them with exsanguinated

visions of a someday that never comes.

French urban developers bulldoze Paris's warren streets so the army can

bring artillery and materiel to bear on future rebels. Agricultural planners move farmers from soil

they know, and soil that knows them, to fields they've never seen, because it

looks better on the map—and famine results.

Well-functioning societies are complicated and interwoven, and

"let's just do it this way,

it'll be so much simpler"-type solutions to complicated and interwoven

problems can do much more harm than good.

•Michael Taussig, The

Devil and Commodity Fetishism in South America—Capitalism is a moral and

behavioral technology. What happens when

people who don't have that technology are exposed to it? I don't mean raised up within it so its

definitions and languages seem natural, I mean exposed to it the way a hand's exposed to a hot stove. The cultures Taussig surveys construct a

mythological framework for basic tenets of capitalism: investments yield

returns because the money literally breeds, and it breeds because it's alive,

and specifically alive with evil intent.

I built most of the conceptual framework for the Craft Sequence before I

read Taussig (and I'd written the first draft of Three Parts Dead), but this book snapped themes and contradictions

into place.

•David Graeber, Debt:

The First 5000 Years—Jo Walton has written eloquently about this book's use

as a piece of worldbuilding inspiration.

I don't want to reinvent the wheel here.

Go ye forth and consult.

•Venkatesh Rao, Tempo:

Timing, Tactics, and Strategy in Narrative Decision-Making—Rao is a

decision scientist, which I didn't know was a thing before I read this

book. And if that sounds to you like it

means "life coach," you're wrong—the Department of Defense, for

example, cares an awful lot about

real time decision-making strategy, and sponsors mathematicians and social

scientists to study the subject. If you grew up in an educational environment

anything like mine, you probably internalized a particular decision-making

method: survey benefits and costs of each decision, and select the objectively

correct path as identified by simple arithmetic. You may even think this is the only way

decisions are made, or at least that this is the only correct way decisions are made.

But it's not, at least according to Rao.

Among its many weaknesses, this method tends to ignore or handwave

tempo, timing, history, and context.

Alternative decision-making methods exist, some more appropriate for

certain situations than for others, and Rao introduces them with real-world

examples. I've recommended this book to

some people who have found it impenetrable, to others who have found it

revelatory. Your mileage may vary. I think it's important.

An observation based on this list: I tend more bro-heavy in

my nonfiction than in my fiction reading.

I need to move some female writers further up the nonfiction TBR

pile. (Long overdue reads: To Serve God and Wal-Mart by Bethany

Moreton, Caliban and the Witch: Women,

the Body, and Primitive Accumulation by Silvia Federici, In Memory of Her by Elizabeth Schussler

Fiorenza, and, on a friend's recommendation, Promises I Can Keep by Kathryn Edin and Maria Kefalas.)

In The Pervert's Guide

to Ideology, Slavoj Zizeck discusses how we're at our most ideological when

we escape from our real world into dreams—because when we escape from the real,

all we have left is ideology. This, it seems to me, is a great danger in

writing fiction, and especially in writing science fiction and fantasy. That's part of the reason I find nonfiction,

especially academic nonfiction, so important: it does not, should not, replace

observing and engaging with the world, but can offer new tools and context with

which to observe and engage.

And with those tools, our escape stands a better chance of crossing

no-man's land to freedom, or something like it.

Some Links:

Bio:

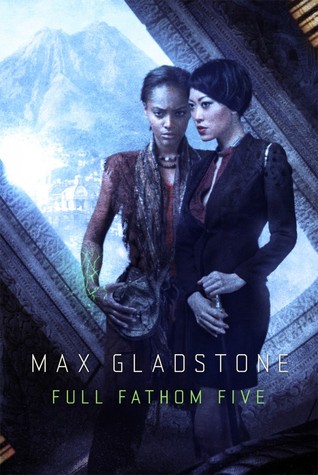

Max Gladstone has sung in Carnegie Hall, been thrown from a

horse in Mongolia and nominated for the John W Campbell Best New Writer

Award. Tor Books published his most

recent novel, FULL FATHOM FIVE, in July 2014.

The first two books in the Craft sequence are THREE PARTS DEAD and TWO

SERPENTS RISE.

Max Gladstone has sung in Carnegie Hall, been thrown from a

horse in Mongolia and nominated for the John W Campbell Best New Writer

Award. Tor Books published his most

recent novel, FULL FATHOM FIVE, in July 2014.

The first two books in the Craft sequence are THREE PARTS DEAD and TWO

SERPENTS RISE.

Book Description:

On the island of

Kavekana, Kai builds gods to order, then hands them to others to maintain. Her

creations aren’t conscious and lack their own wills and voices, but they accept

sacrifices, and protect their worshippers from other gods—perfect vehicles for

Craftsmen and Craftswomen operating in the divinely controlled Old World.

When Kai sees one

of her creations dying and tries to save her, she’s grievously injured—then

sidelined from the business entirely, her near-suicidal rescue attempt offered

up as proof of her instability. But when Kai gets tired of hearing her boss,

her coworkers, and her ex-boyfriend call her crazy, and starts digging into the

reasons her creations die, she uncovers a conspiracy of silence and fear—which

will crush her, if Kai can’t stop it first.

Comments

Post a Comment