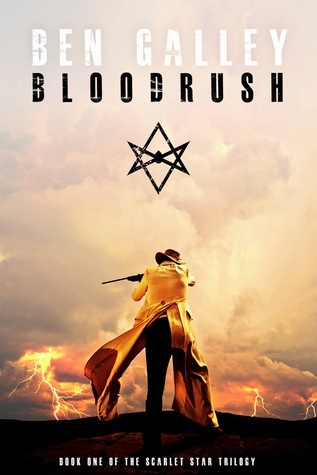

Synopsis:

“Magick ain’t pretty, it

ain’t stars and sparkles. Magick is dirty. It’s rough. Raw. It’s blood

and guts and vomit. You hear me?”

When Prime Lord Hark is found in a pool of his own blood on the steps of his halls, Tonmerion Hark finds his world not only turned upside down, but inside out. His father's last will and testament forces him west across the Iron Ocean, to the very brink of the Endless Land and all civilisation. They call it Wyoming.

This is a story of murder and family.

In the dusty frontier town of Fell Falls, there is no silverware, no servants, no plush velvet nor towering spires. Only dust, danger, and the railway. Tonmerion has only one friend to help him escape the torturous heat and unravel his father’s murder. A faerie named Rhin. A twelve-inch tall outcast of his own kind.

This is a story of blood and magick.

But there are darker things at work in Fell Falls, and not just the railwraiths or the savages. Secrets lurk in Tonmerion's bloodline. Secrets that will redefine this young Hark.

This is a story of the edge of the world.

When Prime Lord Hark is found in a pool of his own blood on the steps of his halls, Tonmerion Hark finds his world not only turned upside down, but inside out. His father's last will and testament forces him west across the Iron Ocean, to the very brink of the Endless Land and all civilisation. They call it Wyoming.

This is a story of murder and family.

In the dusty frontier town of Fell Falls, there is no silverware, no servants, no plush velvet nor towering spires. Only dust, danger, and the railway. Tonmerion has only one friend to help him escape the torturous heat and unravel his father’s murder. A faerie named Rhin. A twelve-inch tall outcast of his own kind.

This is a story of blood and magick.

But there are darker things at work in Fell Falls, and not just the railwraiths or the savages. Secrets lurk in Tonmerion's bloodline. Secrets that will redefine this young Hark.

This is a story of the edge of the world.

find out more about Ben Galley's writing by visiting his website. Here you will also be able to read 4 more additional chapter of Bloodrush!

A Prelude

There are many places in this world where we humans are not

welcome. Antarticus, for example, has slain explorer after explorer with its

wolves and winds so cold and fierce they can cut a man in half. Or the Sandara,

plaguing travellers for millennia with its fanged dunes and sandstorms. Or what

about the high seas, and the Cape of Black Souls, where the waves swallow ships

whole, and never spit them back out? But there are darker places on this earth.

Much, much darker places.

These

are places that time has forgotten, that we have forgotten, now that we’ve turned our attention to industry,

to business, and to science. Our steam and our clockwork may have conquered the

globe, but we have built our cities on old and borrowed ground, a ground that

knew many creatures and empires before it felt the kiss of our own feet. These

were the ages that spawned fairy tale and folklore, dreams and nightmares, the

world that we trampled in our march for progress, burying it beneath cobble and

railroad.

But

stubbornness is a trait of victors, so they say. The vestiges of this old world

are still clinging on, hiding in the dark places, lost in the shadows, glaring

at us from behind their magic. Oh, they are very much alive, friends, hiding in

the cracks of reality, the spaces between your blinks. And woe betide anybody

that dares to go hunting for them. You would have better luck in the Sandara.

Of

course, you have known this all along. If you have ever felt the hot rush of

fear in your stomach when a twig snaps in the twilight woods, then you have

known it. If you have ever felt that chill run up your spine every time you

cross the old bridge, you have known it.

We

humans remember the darkness very well, and how its monsters prowled the edges

of our campfires and snatched us into the night. We simply refuse to acknowledge

it is anything other than irrational fear. Ghost stories. Boogeymen. Old wives’ tales. Nonsense, though we secretly

know the truth. So much so that when we read in the newspapers that a man was

ripped to shreds by a mysterious assailant in the old dockyards last Thursday,

we do not think psychopath, we think werewolf. Maybe we would be right.

There

are dark things in the shadows, and they are far from fond of us humans.

Chapter I

“To the Lost”

18th

April, 1867

‘To the lost.’ The surgeon raised his tiny glass with

a gloved and rather bony hand.

Tonmerion

Hark did the same, though he could only summon the wherewithal to raise it

halfway. He let it hover just beneath his chin, as if he were cradling it to

his chest. The liquor smelled like cloves. Sickening. However he tried, he

couldn’t

tear his gaze away from the pistol, that sharp-edged contraption of humourless

steel and stained oak, lounging in an impossibly clean metal tray at the elbow

of his father’s

body.

‘The lost,’ he murmured in reply, and flicked the

glass as if swatting at a bothersome bluebottle.

A

pair of wet slapping sounds broke the sterile, white-tiled silence as the

liquor painted a muddy orange streak on the milky vinyl floor. So that was that.

What precious little ceremony they must observe was over. Lord Karrigan Bastion

Hark, the Bulldog of London, Prime Lord of the Empire of Britannia, Master of

the Emerald Benches and widower of the inimitable Lady Hark, had been

pronounced dead. As a doornail.

Tonmerion

could have told them that from the start, but such was tradition. His gaze

inched from the gun to his father’s

pallid skin, bruised as it was with the blood settling, or so the surgeon had

told him as he worked. Tonmerion had decided he did not like surgeons. They

were rude; being so bold as to poke around in the visceral depths of other

people. Of boys’ dead

fathers.

His

gaze moved to the neatly sewn-up hole in his father’s chest, directly above his heart. The

oozing had finally stopped. The puckered and rippled edges of white skin around

the black thread were clean. Not a single drop of corpse blood seeped through.

Not surprising, thought Tonmerion, seeing as so much of it had been left on the

steps of Harker Sheer’s western garden.

For

a brief moment, the boy’s

eyes flicked to his father’s

closed eyelids. He thanked the Almighty that those sharp sapphire eyes were

hidden away, not bathing him with disappointment, as was their custom. Even

then, in the grip of cold death, Tonmerion could almost feel their gaze

piercing those grey eyelids and jabbing him. His own eyes quickly slunk away.

Instead, he looked at the surgeon, and was somewhat startled to find the man

staring directly back at him, arms folded and waiting patiently.

‘And what now?’ Tonmerion piped up, his young voice

cracking after the silence.

‘The constable will be here in a

moment, I’m sure.’

‘Is he late?’ asked Tonmerion, biting the inside of

his lip. The body was so grey …

The

surgeon looked a smidgeon confused. He pushed the wire-framed rims of his round

glasses up the slope of his nose. ‘I beg your pardon, Master Hark?’

Tonmerion

huffed. ‘I said, is he late?’

‘No, young Master. Simply finishing the

paperwork.’

Tonmerion

scratched his neck as he tried to think up something clever and commanding to

say. Gruff words echoed through his mind. Get your chin up. Stand straight.

Look them straight in their beady little eyes.

Words

from dead lips.

‘Then he must have been late earlier in

the day. Why else would he not be here, on time, when I am ready to leave.

Instead I am forced to stand here, stuck looking at this … this

…’ His words failed him miserably. His

tongue sat fat and useless behind his teeth. He waved his hand irritably. ‘This

… carcass.’

For

that was what it was. A carcass. So callous in its truth. Tonmerion

could see it in the surgeon’s

face, the condemning curl in that hairless, sweat-beaded top lip of his.

The

surgeon took a sharp breath. ‘Of course, Lordling. I shall fetch him

for you.’ And

with that he turned on his heel, making to leave. The leather of his shoe made

a little squeak on the white vinyl, but before he could take a step, the sound

of heavy boots was heard on the stairs. ‘Ah,’ the surgeon said, turning back with

another squeak. ‘Here he comes now. You shall have your

escape, young Master Hark.’

‘

Yes, well,’ was all Tonmerion’s tongue could muster. He folded his

arms and watched the barrel of a constable emerge from the stairwell. The

constable’s

bright blue coat strained at the seams, pinning all its hopes on the polished

buttons that glinted in the sterile light of the room. Now here’s a man who has seen too much of a

desk and not enough of the cobbles,

his father would have intoned. Tonmerion almost felt like turning and shushing

his dead father.

‘Master Hark,’ boomed

the constable, as he shuffled to a halt at the foot of the table. His eyes were

fixed on Tonmerion’s,

but it was easy to see they itched to pull right, yearned to gaze on the body

of Tonmerion’s

father. Tonmerion didn’t

blame him one inch. It wasn’t

every day you got to meet a Prime Lord, especially a freshly murdered one.

‘My apologies for …’ he began, but Tonmerion cut him off.

‘Apology accepted, Constable Pagget,’ he replied. ‘Have

you captured my father’s

murderer yet?’

Pagget

shook his head solemnly. ‘Not yet, I’m afraid …’

‘Well, what is being done about it?’

‘Everything that can be done, Master

Hark.’

‘Well that’s not …’ Tonmerion began, but it was his turn

to be cut off.

‘Please, young sir, it’s about your father’s will.’

Tonmerion

threw him a frown. ‘What about my father’s will? What and where must I sign?’

There

was a moment of hesitation, during which the constable’s mouth fell slowly open, the ample

fat beneath his chin gently cushioning the fall. Not a single sound came forth

for quite a while.

‘Whatever is the matter?’ demanded Tonmerion impatiently.

Constable

Pagget summoned the wherewithal to shut his mouth, and soon afterwards he found

his voice too. ‘It’s your father’s last wishes, Master Hark, they

concern you directly,’ he

said, his eyes flashing to the surgeon for the briefest of moments.

Tonmerion

huffed. ‘Well of course they do! I’m the only Hark left. The estate will

be left to me,’ he

replied, trying to ignore the truth in his own words. It frightened him a

little too much.

‘Not …

exactly,’ Pagget croaked. ‘That is to say … not

yet.’

‘Yet? What do you mean, yet?’

The

constable took a step backwards and waved a couple of fat fingers at the

stairs. ‘You’d better step into my office, I think,

young Master Hark. We apparently have much to discuss.’

‘This is highly irregular,’ Tonmerion began, his father’s favourite phrase, spilling out of

his mouth. He bit his lip and said no more. Fixing a frown onto his face, the

young Hark raised his chin and went to take a step forwards that said

everything his traitorous mouth could not: a confident step that said he was

inconvenienced, displeased, that he deserved respect, that he was in command

here, and not crumbling with worry and fear and disgust and all those other

things that lords and generals and heroes don’t feel. Sadly, Tonmerion’s

step forwards was quite the opposite. It was a step so lacking in grace and

dignity that Tonmerion would forever shiver at the very thought of it. As his

foot hit the floor with a wet slap, not a squeak, Tonmerion realised his

mistake. The liquor.

His

foot slid away from him, betraying him so casually that his leg, and the rest

of him for that matter, were powerless to resist. Tonmerion performed an

ungraceful wobble and grabbed the nearest thing his flailing arms could reach … his

father’s

dead arm.

A

small wheeze of relief escaped his tight lips as he found himself upright,

safe. A similar sound came forth when he realised what exactly it was that had

saved him from the most embarrassing fall, though this time it was strangled by

horror, and disgust. Tonmerion’s

gaze slowly tumbled down his arm, from the expensive cloth to his ice-white

knuckles, to the dead, bruised, slate-coloured flesh that his fingers were

squeezing so tightly. Tonmerion gurgled something and quickly righted himself,

red in the face and wide in the eyes. He quickly began to smooth the front of

his shirt, but stopped hurriedly when it dawned on him that he had just touched

a dead body. He held his hands out in the air instead, neither up nor down,

close nor far.

‘A cloth,’ he murmured. The surgeon obliged him,

leaning over to pass him a startlingly white cloth from beneath the bench.

Tonmerion dragged it over his knuckles and fingertips, and nodded to the

constable. ‘Lead the way.’

Pagget

had not yet decided whether to stifle a laugh or to share the boy’s revulsion. He simply looked on, one

eye squinting awkwardly, his face stuck halfway between the two expressions.

‘Jimothy?’ the surgeon said, and Pagget came to.

‘Right! Yes. This way if you please.’ He only barely managed to keep from

adding, ‘Mind your step.’

Tonmerion

followed him without a word.

*

‘America.’ Tonmerion gave the man a flat stare

that spoke a whole world of disbelief.

Witchazel

was his name, like the slender shrub, and it was a name that suited him to the

very core. He was more stick than man, loosely draped in an ill-fitting suit of

the Prussian style, charcoal striped with purple. His hair was thin and

jet-black, smeared across his scalp and forehead like an oleaginous paste.

Tonmerion had never liked the look of the lawyer. One with power should

dress accordingly. His father’s

words, once more.

Witchazel

shuffled the wad of papers in his leather-gloved hands and coughed. It meant

nothing except a resounding yes. Tonmerion looked at Constable Pagget, but

found him idly thumbing the dust from the shelves of his ornate bookcase.

Tonmerion looked instead at his knees, and at the woven carpet just beyond

them. He tugged at his collar. The constable’s office was stifling, heavy with

curtains, mahogany, and leather. The news did not help matters, not one bit.

‘And this aunt …’ he asked.

‘Lilain Rennevie,’ filled in Witchazel.

‘Lives where exactly?’

Witchazel’s face took on an enthusiastic curve,

a look of excitement and wonder, one that had been well-practised in the

bedroom mirror, or so it seemed to Tonmerion. ‘A

charming place, right on the cusp of civilisation, Master Hark,’ he said. ‘A

frontier town, don’t

you know, going by the bucolic name of Fell Falls. A brand new settlement

founded by the railroad teams and the Serped Railroad Company. They’re aiming for the west coast, you see,

blazing a trail right across the country in search of gold and riches and the

Last Ocean. An exciting place, if I may say so, sir. I’m almost envious!’ Wichazel grinned.

‘Almost,’ Tonmerion replied drily.

Witchazel

forced his grin to stay and turned to look at the constable, hoping he would

chime in. All Pagget did was smile and nod.

Witchazel

produced a map from the papers in his hand and slid it across the desk towards

the boy. ‘Here we are.’

Tonmerion

leant forwards and eyed the shapes and lines. ‘It

looks small.’

Witchazel

templed his fingers and hid behind them. ‘Yes, but it has so much potential to

grow,’ he

offered.

‘Very small.’

‘You have to start somewhere!’

‘And forty miles from the nearest town.’

‘Think of the peace and quiet. Away

from the hustle and …’

‘It’s literally the end of the line.’

‘Not for long, mark my words!’

‘And what does this say: desert?’

Witchazel’s temple collapsed and he spread his

fingers out on the desk instead, wishing the green leather would magically

transport him out of this office. What a fate this boy had inherited. Whisked

away to Almighty knows where. No mansion. No servants. No money … Witchazel

almost felt sorry for him.

‘Desert, yes. It seems that the

territory of Wyoming is somewhat wild. Deserts and mountains and, oh,

what was the word …’ Witchazel

clicked his gloved fingers, resulting in a leathery squeak. ‘Prairies, that was it. But surely that’s exciting, isn’t it?’

Tonmerion

had crossed his arms. His eyes were back on the lawyer, trying with all his

might to drill right into the man’s

pupils, to wither him, as he had seen his father do countless times. ‘Do

I have any say in the matter?’

Witchazel

made a show of checking the papers again, even though he already knew the

answer. ‘I’m afraid the instructions are very specific.

You are to remain in the care of your aunt until such time as you are of age to

inherit, on your eighteenth birthday. Until then all assets will be frozen in

law, under my authority.’

Tonmerion

let out a long sigh, ruffling the strands of sandy blonde hair that stubbornly

insisted on hanging forwards over his forehead, rather than lying to the sides

with the rest of his combed mop. ‘And what manner of woman is my aunt?’ he asked. He had barely known of her

existence until twenty minutes ago. Now he was staring down the barrel of a

five-year exile, with her and her alone. He felt a lump in his throat. He tried

to swallow it down, but it held fast. ‘Is she the mayor? A businesswoman?’ he croaked.

Witchazel

flipped through a few of his pages. ‘She is a businesswoman indeed, you’ll be pleased to hear.’

Tonmerion

sagged a little in his chair.

Witchazel

peered closely at one line in particular. ‘It says here that she works as an

undertaker.’

The

boy came straight back up, stiff as a board.

*

It

was a day for wanton staring, Tonmerion had decided. He may have escaped the

body of his dead father in the surgeon’s

basement, but now he was trapped by the dried pool of blood on the steps of one

of the Harker Sheer estate’s

many vast patios. The stone beneath was a polished white marble, which made the

blood, even now that it had dried to a crumbling crust, all the more stark.

Tonmerion watched the way it had settled in a thick, rusty crimson slick that

dripped down the stairs, one by one, until it found a pool on the third.

When

Tonmerion finally wrenched his gaze from his father’s blood, he turned instead to the thin

fold of paper he clutched so venomously in his left hand. He held the paper up

to the cloud-masked sun and scowled: tickets for a boat to a faraway land.

Tonmerion didn’t

know which to hate more: the blood or his looming fate.

‘What have I done to deserve this?’ he asked aloud. Unable to bring

himself to utter a response, and having none to offer, he let the sound of the

swaying elms and whispering pines fill the silence.

During

the coach ride home, Tonmerion had pondered every avenue of escape. Once his

mind had drawn out all the possibilities, like wool spilling off a reel,

neither running nor hiding had seemed too fortuitous. He had no money save what

he had found in his father’s

desk: a handful of gold florins, several silver pennies and a smattering of

bronzes and coppers. That would not last more than a few weeks. He had given

complaining a little thought too, but had come to the decision he’d done enough of that in the constable’s office. In truth – in

horrid, clanging truth

– Tonmerion was stuck.

He

was bound for America, the New Kingdom.

That

was the source of the hard, brutal lump wedged in his throat. He lifted a hand

to massage it and tried to swallow. Neither helped. He took a gulp of air and

felt immediately sick. The blood beckoned to him, but Tonmerion steered away

from it. He was not keen to repeat the liquor episode.

Remembering

the water fountain at the bottom of the steps, he let his shaky legs lead the

way. His wobbling reflection in the hissing fountain’s pool confirmed that he was indeed

paler than a sheet of bleached parchment. Tonmerion put both hands on the

marble and dipped his head into the water to let the cold water sting his face.

It was refreshing and calming. He took in three deep gulps and felt the

coldness slide down into his belly. Wiping his mouth, he stared up at the

pinnacles of the pines.

‘By the Roots, you’re white.’

Upon

hearing a voice speak out from the bushes, on an estate that was supposed to be

emptier than a beggar’s

purse, any other person would have jumped, or even squealed with surprise, but

not Tonmerion. He did not flinch, for this was nothing out of the ordinary for

him.

‘He’s dead, Rhin,’ he muttered, still staring up at the

trees.

‘Speak up.’ The voice was small yet still had all

the depth and resonance of a man’s

voice.

‘It’s all going to change.’ Tonmerion looked over at the blood,

stark against the marble, and nodded.

There

was a polite and nervous cough, and then: ‘I’m sorry, Merion, for your father. I

truly am.’

Merion’s gaze turned to the marvellous little

figure standing in the dirt, half of his body still hidden by the shadow of the

ornamental bush – no, not hidden, fused with the bush in some way.

Merion did not bat an eyelid.

‘It’s all changed, just like that,’ he clicked his fingers, and the figure

stepped out of the shadows.

To

say the small gentleman was a fairy would be doing him a great injustice.

Contrary to popular belief, there is a great deal of difference between a fairy

and a faerie. The former are small, silly creatures, more insect than

human, and prone to mischief. The latter, however, are a proud and ancient

race, the Fae. They are larger, smarter, and infinitely more dangerous than

fairies, and bolder. For millennia they have lived unseen in the undergrowth

and forgotten forests, just out of the reach of human eyes and fingers. They

are now nought but folklore, wives’ tales,

rubbish for the ears of children. No man, in his right mind, would believe in

such a thing as a faerie. But here one stood, as bold and as bright as a summer’s day.

Rhin

stood just shy of twelve inches tall, big for Fae standards. He was long of

limb, but not scrawny. Between the gaps in his pitch-black armour, it was easy

to see that the muscles wrapped around his bony frame were like cords, tightly

bunched.

Rhin’s skin was a mottled bluish grey,

though it was not uncommon to see him glowing faintly at night. His eyes were

the only bright colour on his person, glowing purple even in the cloudy

daylight. The thin metal plates of his Fae armour were jet-black, held in place

by brown rat-leather. His boots, rising to just below the knee, were also

black.

And

of course, there are the wings. Thin, translucent dragonfly wings sprouted from

the ridge of Rhin’s

shoulders and hung down his back, hugging the contours of his armour and body

and glistening blue and gold. The Fae lost the power of flight centuries ago.

Their wings are weaker now, but they still have their uses.

Four

years had passed since Rhin had crawled out of the bushes and straight onto

Merion’s

lap, bleeding and vomiting. Merion had been just a young boy, only nine at the

time, and the sight of a strange grey creature with armour and dragonfly wings,

sliding in and out of consciousness, would have frightened any child half to

death, but not Merion.

Rhin

crossed his arms, making the scales of his armour rattle. He tapped his

claw-like nails on the metal. It was in need of a polish. ‘It’s not right, what was done to your

father. Roots know I didn’t

know the man, but he didn’t

deserve this, and neither do you. Neither do we.’ Rhin bowed his head. ‘Like

I said, I’m

sorry, Merion.’

The

lump in the young Hark’s

throat had returned, this time with vengeance. Maybe it was the faerie’s condolences, maybe it was the

crimson streak in the corner of his eye, or perhaps it was the crumpled fist of

papers by his side, Merion didn’t

know, but he knew his lip was wobbling. He knew it was all suddenly terribly

real.

Real

men cannot be seen to cry.

More

of his father’s parting words.

Merion

swallowed hard, and tucked his lip under his top teeth, biting down. He nodded

and, when he trusted himself to speak without his voice cracking, he said ‘Thank

you.’

Rhin

shuffled his feet and ran an absent hand through his short, wild hair.

Jet-black it was, and thick, slicked back and cropped short at the sides. ‘Do

they know who did it?’ he

asked quietly.

Merion

stamped his foot and paced out a tight, angry circle. ‘Pagget

doesn’t

have a clue,’ he

groused. ‘Nobody has any idea.’

‘That’s …’

‘An outrage. Yes, I know. And guess

what? That’s

not even the worst part.’

‘Not the worst …?

What could be worse than …’ the

faerie gestured at the slick of blood on the marble steps. ‘… that?’

Merion

turned and brandished the folded paper. ‘This! It’s

an abomination. A disgrace. An insult!’

Rhin

looked worried. ‘Yes, but what is it?’

Merion

pinched the bridge of his nose and swallowed again. Say it out loud and, who

knows, it just might sound a little better, he told himself. ‘We

have to move to America.’

No,

no better.

Rhin’s lavender eyes grew wide. ‘The

New Kingdom? Why?’

‘My father left instructions, Rhin. All

of Harker Sheer, all of his other estates, all of his money. It’s mine now, but not until I turn

eighteen.’ Merion

aimed a kick at the base of the fountain. ‘And in the meantime I, we, have

to go live with my aunt, in Wyoming.’

‘And where the hell is that?’

‘In the western deserts of America, the

arse-end of nowhere, to put it plainly. Full of filthy rail workers, peasants,

sand, and horses and cows, no doubt.’

Rhin

rubbed his chin. ‘It sounds perfect,’ he said. Merion was about to snort

when he realised there hadn’t

been the faintest tremor of sarcasm in Rhin’s words. He stared down at the faerie.

‘You’re serious?’

Rhin

shrugged. ‘It’s the perfect escape.’

‘Yes, for you maybe. I suspected you

might like this god-awful fate of mine. Not all of us are runaways and

outcasts, Rhin. I’m

not in hiding. I have a future here, in London. I have a great

responsibility to inherit, and a murderer to catch, for Almighty’s sake! My father must have justice.

The Hark name needs protecting …’ Merion

trailed off, flattened by the impossibility of it all. ‘I

can’t just leave. I can’t

just let it fall to the dogs.’

‘You’re thirteen, boy.’

Merion

flapped his hand. ‘But I’m the only one left! It’s my duty. And don’t

call me boy, you know I hate that.’

Rhin

took a step forwards, eyes wide. ‘You would still have to wait until you

were eighteen, even if you father hadn’t

been killed.’

‘Murdered, Rhin. Murdered.’ The fountain received another kick. ‘And

no difference, you say? Hah! At least if he was still alive, I could have lived

my life in comfort, in society, within reach of the capital. But no, he was murdered,

and now we have to go live in a shack in some place called Fell Falls. No

dinners, no balls, no trips on the rumbleground trains, no visits to the

Emerald Benches. Nothing. Sod all.’ It

was at times like these that Merion wished he’d asked the kitchen staff to teach him

more swearwords.

Rhin

was not convinced. ‘All I heard was no tedious ceremonies,

no politics, and no father watching your every move, no offence. We can be free

in America, Merion. Free to do what we want, safe in the knowledge that you can

come back to this, to a fortune and a life in high society.’

‘In five bloody years!’

‘More than enough time to turn you into

a proper man, to toughen you up. Not like one of these silk-clad dandies you

idolise. A man with rough hands and bristle on his cheeks—ladies

would love that.’ Rhin

dared as much to wink. Merion pulled a face.

‘Rubbish.’

‘Trust me, I know. Listen to your

elders.’ Rhin

was over two hundred years old. He had a point.

Merion

slumped in every possible way a person could slump. He crumpled to his knees

and then to his backside, letting his shoulders hang like loose saddlebags and

his hands splay across the marble. ‘I just don’t

know. I can’t

put it into words. The world is upside down.’

Rhin

walked forwards to put a small hand on Merion’s knee. ‘It

doesn’t

have to be a punishment, Merion. It could be an adventure, something that could

change you—put some fire into your belly. Five

years isn’t

that long a time.’

Merion

snorted. ‘Easy for you to say.’

‘Are we in agreement. Adventure?’ Rhin asked.

With

great solemnity, Merion lifted his head and stared up at the roiling grey

skies, not a patch or stray thread of blue anywhere to be seen. Merion was

going to miss these skies, and their rain, the staple of the Empire. He let the

cold breeze run its fingers across his neck and face, savouring that moment. He

swallowed one last time, and found that the lump had disappeared—for

now, at least.

‘I’ll let you know when we get there,’ replied the young Hark.

Comments

Post a Comment